Understanding Cloud Datacenter Economies of Scale

James Hamilton’s recent MIX’10 presentation on economies of scale for large cloud providers was quite impressive. James “gets it” like few others in the industry. If you haven’t watched his hour-long presentation, I suggest you do. I also recommend this excellent response from James Urquhart. My goal in this posting is to highlight, clarify and expand on a few of James Hamilton’s points. I will focus on Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS) clouds, but the concepts are relevant for other kinds of cloud services.

In his presentation, James focuses on power: utilization, distribution, etc., and while an important element, like him, I don’t think it’s the most important factor.

I also want to dispel the myth that only the largest companies can achieve these economies of scale. Don’t get me wrong; providing a cloud service is a scale game. It requires a certain amount of buying power to compete. However,you don’t need to be MSFT, YHOO, AMZN, or GOOG to compete effectively. Buying power can be had at levels much lower than you might think.

In this article, I refer regularly to Jame’s comments in his presentation, so I suggest you watch his video first. In order to minimize confusion, I’ve borrowed some pictures from his slides and inserted them here for your reference. This is a long entry, but it will be worth the read as I’ve got numbers for you which I hope you will find interesting.

Background

Like James, the Cloudscaling team has a history of building large scale services. I’ve worked in this area for 16+ years as has our COO, Adam Waters, and several of our team members. Understanding of the economies of scale, especially for service providers, cloud or otherwise is fundamental to our DNA. For example, see my previous piece describing how oversubscription works.

Enough of that! Let’s dig in and look at where you can achieve economies of scale, identifying areas James Hamilton may have neglected, and clarifying areas where I think there is still confusion.

Economies of Scale

There are a number of areas where you can achieve economies. James touched on a few in his talk. While this is not a 100% complete list, here are key areas of opportunity that I see:

-

Datacenter and facilities architecture (power & cooling)

-

Buying power (COGS) for Networking, Compute (Servers), and Storage

-

Development & Labor Costs

-

Standardization & Homogenization

-

Cash Flow

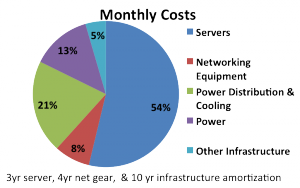

In James Hamilton’s model (see pie chart below) server costs are the dominant cost, but he critically left out development & labor costs. This can be as much as 10% for a cloud and while it’s possible for large clouds to drive this down to a marginal cost, in practice there are no Infrastructure-as-a-Service clouds of sufficient size to achieve this yet. While James focuses primarily on power & cooling in his presentation, let’s take a closer look at some other areas.

James Hamilton’s Distribution of Cloud Datacenter Costs

James Hamilton’s Distribution of Cloud Datacenter Costs

Networking

There are two key areas of networking where you can achieve economies of scale:

-

Buying IP (network) transit (OpEx)

-

Capital expense (CapEx)

Unfortunately, James provides one example with numbers from 2006 which compare two companies purchasing bandwidth. The larger company purchased bandwidth at $15 per Mbps per month at the 95th percentile ($/Mbps/mo) vs the smaller company’s expense of $95/Mbps/Mo. James uses this number to show a 6 or 7 to 1 buying power difference.

The IP landscape has changed dramatically since 2006. It’s a dirty little secret in the hosting and cloud world that bandwidth is dirt cheap[1]. In fact, you need very little buying power to get rock bottom prices. Street price for high quality Tier-1 IP transit is <$5/Mbps/Mo if you buy 1Gbps commits. That’s a mere $5,000/mo, which is well within the spending range of even small companies. My local coffee shop could probably afford it. Yes, it’s quite possible larger buyers are getting even lower rates than $5/Mbps, but there is a bottom and it’s not much less than $5/Mbps/Mo so the disparity in buying power is closer to 3:1 or 2:1.

To give you some perspective, I know for a fact that some Yahoo! datacenters push upwards of 40Gbps. A lot, certainly, but at $1-3/Mbps, well within the buying capacity of even medium size businesses.

The second area is using buying power to purchase network hardware at much reduced rates. When buying bulk quantities of network gear, the theory is that network costs can be significantly reduced, hence larger players have significant cost advantages. Unfortunately, this only works partially in practice. Network equipment costs are still increasing significantly, not reducing as with compute and storage equipment costs. Combined, networking equipment (CapEx) and power usage (OpEx) make up 21% (in the piechart above) of datacenter costs and both are steadily increasing.

Large cloud providers are beginning to address this by systematically removing brand name networking vendors like Cisco and Juniper[2]. It is now possible to buy very high quality, exceptionally cheap networking gear direct from Taiwanese manufacturers. Many of these are the original equipment manufacturers for name brands.

Most people don’t realize how marked up Cisco/Dell/HP/Juniper gear is. For example, these Taiwanese OEMs have networking gear with price points as low as $100/10GE port. Yes, $100 per 10Gig Ethernet port. That’s about 1/10 the Cisco price point. At the same time, the quality of the gear is quite high and in some cases the components and chips are a generation ahead of what’s available from the name brands.

In other words, times are changing. We’re going to see a significant drop in the prices for networking gear across the board for the first time in ages and hopefully networking will get in line with the standard Moore’s Law curve.

Servers

Flogged. Dead Horse. There isn’t any significant buying power to be had in the commodity x86 server market. x86 server vendors, particularly those providing commodity offerings, have thin margins to begin with. 25% is typical. An Amazon or a Google can push these down somewhat by buying in bulk, but not enough to give them more than a marginal advantage. Anyone who can buy $1M USD of servers at once can negotiate a pretty steep discount. Many businesses can afford to buy at that price point.

James Hamilton understands this and points out where the real buying power is: buying customized hardware in bulk that allows for datacenter optimization and cost reductions in power, cooling, and space. By purchasing customized server offerings from the likes of an SGI/Rackable or Verari that include well spec’ed components, designing for their particular datacenter environment there are significant savings to be had. That’s where the real opportunities lie.

Vendors like SGI/Rackable and Verari can afford to build to spec in large quantities and amortize that customization across large orders. These vendors are learning from the large clouds what works best and productizing it. You will be able to benefit from this learning and productization too. In fact, we help our clients figure out these kinds of issues every day and know that these opportunities are within the reach of all types of cloud businesses.

Development & Labor Costs

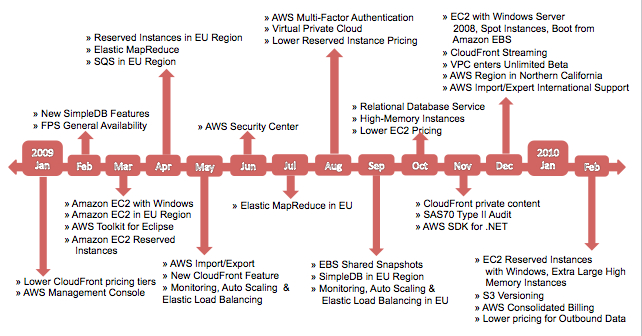

Although touched on only briefly in the presentation, but I think this is the heart of the matter. Amazon leads the pack in rapid development of cloud services (see my post “Is Amazon Winning the Cloud Race?”). Their ability to innovate both automation and technology allows them to drive significant economies of scale. This implies that development is a much larger cost of a cloud than might be expected.

Amazon’s EC2 was initially built using a 15 person engineering team. I estimate that AWS as a whole probably has 50+ software engineers and 20-30+ support and operations staff [3]. Last year, I estimated there were approximately 40,000 servers at a target price of $2,500 each for EC2. That’s 100M in CapEx on servers. A reasonable estimate of engineering and operational labor costs for AWS are probably close to 10-20M over the past 4 years. A not inconsequential number compared to the CapEx costs.

One client recently asked us to compare the operational expense costs for server administration between large clouds (e.g. Microsoft and Google) and a typical enterprise. Usually, enterprises can manage 100-200 servers per admin. Microsoft’s stated goals are 1,000-2,000 for their Chicago datacenter (confirmed in the presentation). Google is managing at the scale of 10,000 servers per admin and trying to get to 100,000.

If you do the math, the basic cost for administration is $75/mo/server for the enterprise, $7.5/mo for Microsoft, and a mere $.75/mo for Google, a 100x difference! When calculating the long term TCO, you’ll find that investing heavily in automation is a “no-brainer” for those whose core competency is building at scale and operating IT at the lowest cost possible[4].

The lesson here, which James alludes to in his presentation (see his map of AWS releases in 2009 below), is that one major economy of scale is the ability to have significant resources deployed for software development purposes. The outcome of most cloud software development is generally automation or technology that enables the business to scale more efficiently.

James Hamilton’s map of 2009 AWS releases

James Hamilton’s map of 2009 AWS releases

Standardization & Homogenization

Often overlooked is that businesses built at cloud scale must run relatively homogeneous environments. By standardizing, they can achieve reasonable scale. For example, Google is reputed to run as little as five hardware configurations across its one million+ server base. In contrast, a typical enterprise has hundreds of configurations across a much smaller server base, increasing operational overhead and expense dramatically.

Did you know that the primary driver behind Yahoo!’s cloud computing initiative was to normalize and cleanup their 800+ configurations? It’s impossible to operate at massive scale without homogeneity and standardization. A huge benefit of virtualization in cloud environments is that it allows the standardization of the physical hardware platform while running a plethora of operating systems at the virtualized layer. This is also why I am occasionally a little sad when I see large enterprise IT shops insisting on purchasing their x86 server hardware vendor of choice. It just doesn’t matter any more. Not if your cloud (internal or external) is designed correctly.

The Cash Flow Problem

A less understood, but just as interesting area of business scalability for clouds is the interplay of growth, speed, and cash reserves. There’s no question clouds can be very profitable and attractive for operators given their high margins and 100% compound annual growth rates (CAGR). Typical payback periods on installed cloud hardware average a fast 3-6 months. However, new entrants need to plan for an extended period of ever increasing hardware expenses that stay well ahead of free cash flow. Larger clouds will require $10M in liquidity to meet their rolling hardware acquisition needs, and even small clouds need to think about acquiring hardware at $1M per step. One key in building a highly profitable cloud lies in minimizing the lag between hardware acquisition and revenue generation. The difference between days and months is the difference between profitability and disaster.

A Brief Aside on ‘Utilization Rates’

And that brings up an interesting point I want to address, which is not technically an economy of scale, but worth discussion. I’m intrigued by the notion that ‘utilization rates’ are almost completely meaningless in the context of public cloud providers. James Hamilton’s claims 30% server utilization (presumably CPU??) as a high metric even for cloud service companies. However, this doesn’t matter when you sell your capacity like an IaaS cloud does. Here’s why: whatever your particular cloud business model is (e.g. selling RAM, CPU, or ‘bundles’ like Amazon’s instances), you must sell as much of it as possible at any given time. Anything else is business suicide. You can’t overbuild and only have 30% of your capacity sold.

Most IaaS providers target 75-80% sold capacity. Their cloud is therefor ‘utilized’ at 75-80% in that the capacity is sold, even if not at 100% usage itself. Unlike a business where unused capacity is waste, in a business model that sells capacity, unused capacity is unsold capacity and hence, not competitive. Not all usage of the term ‘utilization rates’ is the same, especially when discussing an IaaS cloud[5].

Conclusion

It’s critical to understand the potential economies of scale for cloud providers. They can achieve these economies through size and focus. While larger players have some advantages, many businesses can afford to buy servers and network in enough bulk to see significant price savings. More important than sheer size is the ability to focus on innovation.

Public cloud providers have a core competency that involves delivering IT services at a very cost effective price point. They are the new IT utility companies of the near future. Their ability to focus and spend development resources to achieve ever newer economies of scale will be something that traditional businesses can’t compete with. Traditional enterprise IT vendors will likely continually be playing “catch up” and be unable to provide competitive solutions in time.

Economies of scale are why other business infrastructure in the past, e.g. railways, telecommunications, and shipping, have consolidated into businesses who focus on delivery of the infrastructure as a core competency. To think IT is any different is to bet against history.

UPDATE: Added footnote to clarify that AWS is currently aggressively hiring so my initial estimates on engineering staff size are way off.

[1] This means most hosting providers and clouds see very large markups on bandwidth. They buy it cheap, but don’t typically pass on the cost savings to smaller customers.

[2] If you listen carefully to Jame’s Hamiltons presentation he alludes to this several times.

[3] It was pointed out in the comments that AWS currently has 100+ technical positions open, so I’m probably very off on my initial size estimate. It’s hard to derive how big the AWS engineering team is from open positions because it depends on their aggressiveness at hiring. A wild guess, assuming the answer is ‘very aggressive’, would be 200 engineers, putting their current operational costs for headcount around 30M annually.

[4] Unlike James Urquhart, in his response, it’s seems apparent to the Cloudscaling team that cost-effective and enterprise-class high-quality clouds are not mutually exclusive.

[5] Check out this tangentially related Wikipedia article on capacity utilization rates for the production base of nations.