Will Containers Replace Hypervisors? Almost Certainly!

After OpenStack, the number one topic that I get asked about these days is containers and their prospects for the enterprise and cloud-native applications. The prospect of containers replacing hypervisors such as VMware ESX or Linux KVM (the default for most OpenStack deployments) is of keen interest to many. Yet, there is confusion. Many people can’t distinguish the difference between containers and VMs. Still others like to wave the security boogeyman in favor of VMs, believing that containers can’t be secure.

Lost in all of this is a proper understanding of not only what a container is at the infrastructure layer, but also what it can be in the future with relatively trivial updates. Also lost is an understanding of the value of traditional hypervisors such as VMware ESX, which is rapidly fading. From my perspective the day of the VM is fading and it’s only a question of how fast the change occurs.

In the interim, should containers run on top of VMs? Or will containers on bare metal simply replace the hypervisor completely?

Finally, what is OpenStack’s place in this? Unlike ESX, OpenStack isn’t a hypervisor, and in fact, can play nice with containers, VMs, or bare metal equally well.

Let’s discuss.

Containers as Infrastructure vs. Containers as Application-centric Packaging and Management Tools

Perhaps I will talk more about this in future, but it’s important to understand that, unlike VMs, containers have a dual lens you can view them through: are they infrastructure (aka “lightweight VMs”) or are they application management and configuration systems? The reality is that they are both. If you are an infrastructure person you likely see them as the former and if a developer you likely see them as the latter.

This points to a de facto path to flattening some parts of the cloud stack and the ability to simplify much of the underlying infrastructure and how it interacts with the application. In a future posting I may take a look at this in much more detail.

For this blog posting, I’m looking at containers primarily through the lens of being an infrastructure tool.

When Hypervisors Died

The death knell of the hypervisor was sounded when Intel provided much of the unique capabilities of the hypervisor directly in the chip via the Intel-VTx instruction set. Prior to this, VMware and Xen had two unique approaches to providing hypervisor capabilities: binary translation and paravirtualization respectively. Arguments raged about which was faster, but once Intel-VTx came along, by virtue of being on the chip die, it was the de facto speed winner. After that, VMware ESX and Xen both used Intel-VTx by default. This also allowed the creation of KVM which depends 100% on the Intel-VTx chipset for these capabilities. Perhaps most importantly, it negated most of the differences between “type-1” and “type-2” hypervisors.

Now, of course, you could argue, that hypervisors still provide value, but this value is not what it was and is primarily focused around providing support for legacy applications in heterogeneous environments. In effect, a hypervisor allows you to run differing operating systems within your guest systems (VMs).

Let me explain.

The Paravirtualization Driver Layer in Hypervisors

Once Intel-VTx came about, the big problem for managing existing legacy “pet” workloads was supporting a wide variety of operating systems. This is what exists in enterprise environments today and support for heterogeneous environments is critical to supporting them. Unfortunately, while you can run an unmodified kernel on Intel-VTx, system calls that touch networking and disk still wind up hitting emulated hardware. Intel-VTx primarily solved the issues of segregating, isolating, and allowing high performance access to direct CPU calls and memory access (via Extended Page Table [EPT]). Intel-VT does not solve access to network and disk, although SR-IOV, VT-d, and related attempted to address this issue, but never quite got there. [1]

In order to eke out better performance from networking and disk, all of the major hypervisors turn to paravirtualized drivers. Paravirtualized drivers are very similar to Xen’s paravirtualized kernels. Within the hypervisor and it’s guest operating system there is a special paravirtualization driver for the network or disk. You can think of this driver as being “split” between the hypervisor kernel and the guest kernel, allowing greater throughput.

Still, performance hits for networking and disk can be anywhere from 5-30% depending on workloads. Paravirtualized drivers simply can’t operate like bare metal.

In addition to having performance issues, paravirtualized (PV) drivers have other issues. For one, PV drivers are written by the various operating system vendors and you need different PV drivers for each hypervisor (ESX, Xen, KVM, etc.) and for each guest operating system (Windows 7, Windows 10, RHEL, Ubuntu, FreeBSD, etc.). This results in a lot of code, a greater attack surface for would be attackers, a huge support and testing matrix, and significant variance in quality.[2]

Most importantly, at this point, the hypervisors themselves are really just a layer to support PV drivers, which themselves are a layer for supporting heterogeneous operating systems.

And one has to ask: “For how long will we have heterogeneous operating systems in the enterprise datacenter?”

The Homogenization of the Enterprise Datacenter Means Containers Win Ultimately

As we move towards cloud native applications and the third platform, we are all keenly aware of the need to standardize and normalize the underlying operating systems. You can’t get greater operational efficiency if you are running 20 different operating systems. If you desire containers, then you are also looking at running them on homogeneous or mostly homogeneous environments. If you are moving to any kind of PaaS platform, you are standardizing the underlying operating systems. Everywhere you look, we’re moving away from heterogeneity.[3]

In such an environment the value of the paravirtualization driver layer (and hence hypervisors more generally) seems pretty thin or perhaps non-existent.

The primary argument for the hypervisor is around supporting pet workloads that require advanced features like VMware DRS and HA for their availability, operating system heterogeneity, and “greater security” via isolation.

Unfortunately for the hypervisor, all of this is coming to fruition in container land one way or another. Except perhaps heterogeneity, which is simply becoming a non-issue.

Containers and Security

It’s a popular refrain to talk about containers as being “less secure” than hypervisors, despite the fact that for some of us, containers were originally conceived as an application security mechanism. They allow packaging up an application into a very low attack surface, running it as an unprivileged user, in an isolated jail![4] That’s far better than a typical VM-based approach where you lug along most of an operating system that has to be patched and maintained regularly.

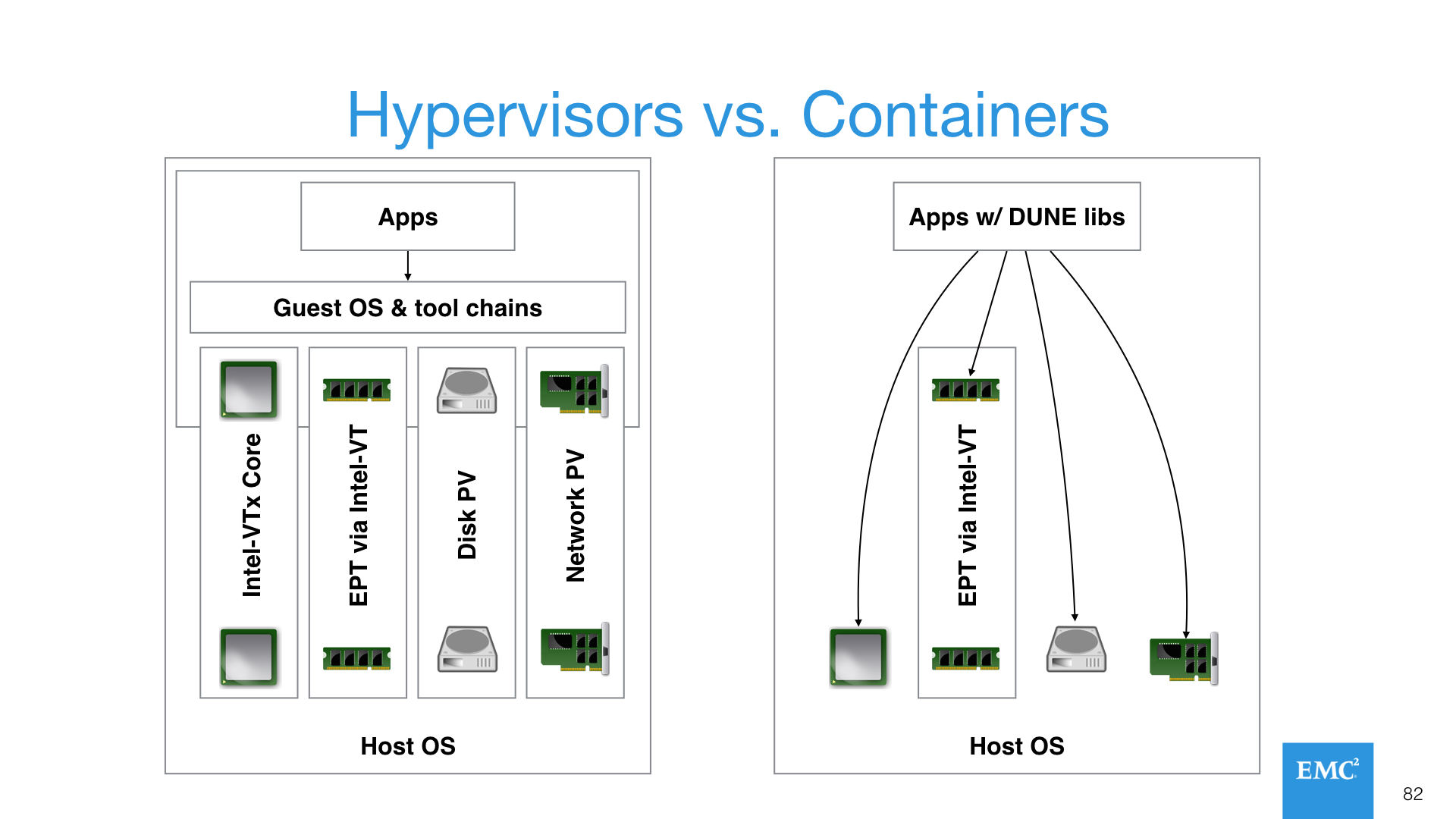

But many will point to the magic voodoo that a hypervisor can do to provide isolation, such as Extended Page Table (EPT). Yet, EPT, and many other capabilities in the hypervisor are no longer provided by the hypervisor itself, but by the Intel-VTx instruction set. And there is nothing special that keeps the Linux kernel from calling those instructions. In fact, there is already code out of Stanford from the DUNE project that does just this for regular applications. Integrating it to container platforms would be trivial.

You can expect Intel to continue to enrich the Intel-VTx instruction set and for the Linux kernel and containers to take advantage of those capabilities without the hypervisor as an intermediary.

Combined with removing most of the operating system wrapped arbitrarily around the application in a hypervisor VM, containers may actually already be more secure than the hypervisor model. But we can say for certain that given time this will certainly be true.

Containers and Resiliency

We then must ask the question: “what about DRS and HA?” Taking aside the fact that these capabilities are largely about supporting pet workloads and that containers don’t play in this world, the reality is that DRS and HA are largely unnecessary in an elastic third platform world. Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS) tools like Cloud Foundry, container management systems like Kubernetes, Rancher, Mesos, and similar management tools are already designed to dynamically scale your workloads. They detect performance and failure issues within your running application and take proactive steps to deal with them.

This then leads us to understand that hypervisors sole value resides primarily around supporting many operating systems using PV drivers, something that is not a requirement in the next generation datacenter.

The Change in Pictures

To help you grok what this change might look like, here’s a view of what the end game is, which assumes that hypervisors “win” in the second platform and are a key tool for supporting legacy workloads, while containers “win” in the third platform for cloud native applications, and become the primary tool to enable modern datacenters and their workloads.

This is a somewhat simplistic diagram, but what I’m trying to show here is that if you don’t care about multiple guest operating systems, if you integrate the DUNE libraries from Stanford into the container(s), if you depend on standard Linux user permissions, if you just talk directly to the physical resources, containers are:

- Highly performant

- Probably as secure as any hypervisor if configured properly

- Significantly simpler than a hypervisor with less overhead and operating system bloat

This third point is worth going into a bit more detail on. It will require a future blog posting to maybe go into it in detail, but here’s the basic 101. A container-centric model not only significantly simplifies the application architecture as you can see above, eliminating excessive layers and bloat from the hypervisor layer, but it also allows for further “flattening” of the infrastructure stack. What do I mean by that? I mean, that as we become container-centric, we’re inherently becoming application-centric. Apps don’t care about the infrastructure topology. How many disks they have, of what kind, and what networks. None of that stuff really matters. The apps and modern cloud-native app developer just cares about the infrastructure contract: I call an API, I get the infrastructure resource, it either performs to it’s SLAs or doesn’t, if it doesn’t I kill it and replace it with another, and if I start to run out of oomph with the infrastructure I ordered, I order another one (horizontal scaling).

I think it’s certainly worth consideration that hypervisors and “pet” type mentality drag us into making overwrought, complex infrastructure topologies that are simply unnecessary for modern applications.

OpenStack + Containers or OpenStack vs. Containers?

For some, there is a question of whether cloud native applications and modern datacenters are dominated by OpenStack or the container ecosystem. For others, these systems work together. There are equally good arguments on either side. On one hand, OpenStack can look like a complex, overwrought attempt at ocean boiling for Infrastructure-as-a-Service (IaaS). On the other, there is no other ecosystem that is as comprehensive, including DNS services, networking services, storage, VMs, bare metal, containers, database services, key management, and so on.

Things might be further confused in that if you look at the primary “PaaS” platforms on OpenStack(PDF) are all container-based (Kubernetes, Cloud Foundry, etc.). More and more, customers choose to use OpenStack and KVM VMs as a substrate to run on top of. And perhaps container-based platforms such as CloudFoundry provide the ultimately tool for corralling and hiding the complexity of OpenStack for the average enterprise developer.

A go forward path that already looks like it’s happening is that hypervisors and containers coexist in the short to medium term, but that as time goes on, the stack flattens and we begin running containers directly on bare metal systems, cutting the hypervisor out, simplifying the stack, while providing greater security, availability, and performance. Ultimately we wind up with a picture that looks like above.

The Ship Has Sailed

From my viewpoint, the ship has sailed on hypervisors. It’s now a container world for the next generation of cloud native applications and it’s only a matter of time before we get there. In the meantime, running containers on top of virtualization substrates is a common way to “just get started”, while the underlying technologies get better and better at running containers directly on bare metal. The modern datacenter will be relatively homogeneous, just like the web scale companies who brought us cloud computing. It will host predominantly cloud-native applications which will manage their own resiliency using platforms like Cloud Foundry, and it will be more secure and higher performance, with much greater levels of utilization, than ever before primarily due to the trajectory of containers and their ecosystem.

I like what I see and I think you do too.

[1] A conversation for another blog posting.

[2] In effect, there are significantly more lines of PV driver code than the hypervisor code itself.

[3] Yes, it’s going to be a while before we get there, but the change is in full swing.

[4] Admittedly, the default configuration of many container systems, like Docker, used to be terrible (running containers as root by default), but that is finally changing.