Subscription Modeling & Cloud Performance

An infrequently talked about, but very important aspect of cloud computing performance is ‘oversubscription’. Oversubscribing is the act of selling more resources than you actually have to customers on the assumption that the average usage will be equal to or less than the actual resources on hand. This is the de facto practice within the hosting and service provider market and has been from the get-go.

For example, typically most Internet Service Providers (ISP) oversubscribe their backbone bandwidth. You won’t notice because most of the time you’ll get your full bandwidth. Why? Because even during peak traffic times not everyone is using the network. Perhaps many or most of the folks in a given area might at any one time and service providers try to develop a subscription model that is as efficient as possible, giving most users their full bandwidth, most of the time, while allowing the provider to keep their costs down.

What happens when a service provider is wrong? Ever been to some kind of major event where a huge number of people converge in a very small area? Have you been unable to get or receive cell phone calls? That’s what happens. Even telecommunications companies and wireless providers oversubscribe.

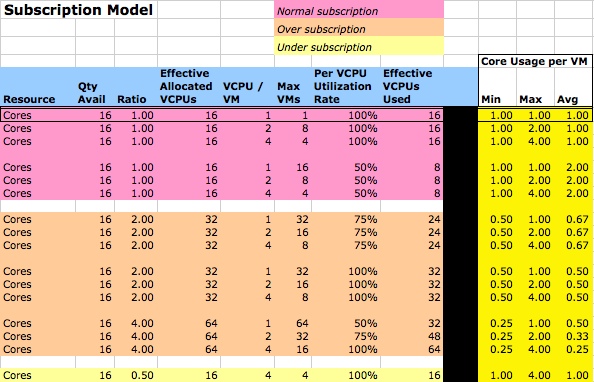

Understanding Subscription Models So, if oversubscription is the de facto standard and if it’s done improperly it could affect your cloud deployments (cloud user) or bottom line (cloud provider), let’s look at a simplified example of building a subscription model. The following image is an Excel spreadsheet that models CPU subscription rates [1] (click through to download the original Excel spreadsheet):

Subscription Modeling (click to download)

Subscription Modeling (click to download)

For this example, the very first row in the table represents a baseline. We’re assuming:

-

single physical server with 16 physical cores

-

a subscription ratio of 1-1 (normal subscription)

-

an allocation of 1 virtual CPU (VCPU) per VM

-

1 VM total on this physical host (this is our baseline)

-

The VM is using 100% of it’s VCPU

For the baseline only, ignore ‘Effective Allocated VCPUs’ and ‘Effective VCPUs Used’. These are artifacts of the formulas I’m using and I didn’t remove them before generating this table.

On the right hand side you’ll see that in our baseline model our VM receives 1 minimum physical core of usage, can burst to a maximum of 1 core, and averages 1 core of usage (because it’s using 100% of it’s VCPU).

The rest of the pink rows following our baseline are all ‘normal subscription’. Meaning the cores are not oversubscribed. For example, row 3 (2nd after the baseline) shows us the effect of allocating 4 VCPUs per VM. This means we can only have 4 VMs max on that server without oversubscribing. Each VM gets a minimum of a single physical core and can burst to 4 cores.[2]

More interesting are the following peach colored rows that show oversubscription models. Taking the very first row where we’re oversubscribing at 2-1, we’re effectively saying: we will sell 32 VCPUs for our 16 physical CPU cores. At 1 VCPU per VM, we can now fit 32 virtual machines on a single physical server (2x our normal subscription rate at it’s best). We now know:

-

Each VCPU gets a minimum of 50% (when running at 100% utilization for all VCPUs)

-

The most each VM can consume is 1 VCPU (we only allocated 1 each)

-

Running at an average utilization of 75% per VCPU, each customer gets 2/3rds of the VCPU they bought

This is a very crude model. It doesn’t take into account mixing different size VMs on a single physical host and a host of other factors [3]. What it does show you is that your cloud hosting provider’s oversubscription model can directly impact your cloud applications hosted on their infrastructure.

Remember, oversubscription can happen for disks, memory, CPUs, and network bandwidth.

Oversubscription in Clouds Today Most cloud providers oversubscribe cores and disks currently. One of the few exceptions that I’m aware of is Amazon’s EC2. My understanding is that they do not currently oversubscribe cores, but they almost certainly oversubscribe disks, particularly on small instances. This is from inside knowledge. You will find folks who are measuring ‘stolen time’, but I suspect this has to do less with it being allocated to other VMs and rather more likely being stolen by the host itself[4].

The moral of this story? Proper cloudscaling requires understanding how oversubscription works.

If you’re a cloud hosting provider, PLEASE do the math; don’t fly by the seat of your pants. Figure out the sweet spot where you can oversubscribe resources, but give your customers (on average and for peak loads) good value for their money.

If you’re a cloud user, you need to recognize that your application’s performance may be impacted by how your cloud provider does oversubscription. Don’t be afraid to ask how they model their oversubscriptions. Don’t be afraid to measure OS performance yourself. If you’re using Linux, make sure you measure how much stolen clock time you see. Regardless of your platform, if consuming cloud storage, instrument your application so you can see when there is variability in or increased latency of that storage [5].

[1] I am not a real business analyst, I just play one on TV, so take this chart with a grain of salt. A big one. [2] I think my formula broke here for average cores. [3] To have a proper model, you would need to have a combinatorial model that took into account RAM, CPU, disk, and networking; BTW, Xen doesn’t allow oversubscribing RAM, but VMware does. [4] Elastic Block Store (EBS) and similar are not ‘free’; since EBS is almost certainly iSCSI-based, any significant usage of your EBS volumes will require not inconsequential CPU usage by the physical host server. [5] If you’re a Rails user, check out NewRelic, who have some tools in this regard; if you’re not, take a look at collectd or Reconnoiter to do it yourself.