Continuous Delusion at the Infrastructure Layer

In the DevOps mythos or worldview, continuous delivery (“CD”) is considered one of the holy mantras. Unfortunately, many take CD to an extreme that is unwarranted and not even reflected in how the DevOps originators (e.g. Amazon, Google) operate. This is one of those situations where folks are extrapolating and providing an interpretation of DevOps that isn’t really accurate. The foundational problem is that all code update and delivery problems are treated equally, when they really aren’t equal. The reality of continuous integration (CI) and continuous delivery (CD) or “CI/CD” is that code deployment risk varies by application. Variance in risk means that there must be variance in testing and frequency of code deployments.

One reason this is true, for example, is that the CI/CD story of success requires several key items. First, that code changes are relatively small, reducing risk. Second, that code changes are frequent. Third, that one side effect of small and frequent is that issues can be fixed with a “roll forward” instead of a “roll back.” Meaning that if a mistake is made or a bug introduced, you simply turn the crank one more time and release an update. Or, for those of you who watched John Allspaw’s presentations on Flickr “Dev and Ops” methodologies in the early days of Velocity Conference (DevOps before the term was coined!), the ability to turn off troublesome features (“feature flags”) in real time (as opposed to a roll forward).

But what happens when your code deployment breaks everything and a roll forward is no longer possible? This issue is, unfortunately, glossed over by many. And that’s because much of the original thinking of a rapid CI/CD release pipeline was focused around websites and the application layer. It has largely ignored the infrastructure layer. Infrastructure is more sensitive to a catastrophic change because if the infrastructure fails, everything fails. In effect, the “blast radius” of infrastructure failures is significantly larger than that of application failures.

Good bye code updates, hello shit show.

Lately I’m seeing more and more magical thinking that CI/CD can be applied equally to the infrastructure layer and it simply can’t.

Let’s dig in further.

Background

In the early days of “DevOps”, before the term was really coined, the hotbed of activity was around small meet ups and the Velocity Conference. I remember at one of the early Velocity Conferences (probably 2008 or 2009) hanging out with many of the early folks in this space. We were fortunate to have some of the Amazon team there who shared in confidence about Amazon.com’s Apollo system that was used to do “thousands of deployments per day.” These were the first glimpses into the pioneering tool work the web scale folks had done around “DevOps”. As most of you know, DevOps origins were about breaking down the “responsibility barrier” between developer and operators, which simultaneously required a re-think of the tools used to manage and deliver site updates.

Amazon’s Apollo system put the deploy button in the hands of the developers. Pre-AWS services had been deployed inside of Amazon that allowed for developers to “order up” compute, storage, networking, messaging, and the like. Much of this work is what inspired Amazon Web Services (AWS) and also the tooling work developed around “DevOps” and rapid CI/CD release pipelines.

However, most of this work was done at the application layer and some of it at the platform layer. Very little of a rapid release was performed around the infrastructure layer itself.

Somehow, this work and the general sentiments of the DevOps community have erroneously performed a straight line extrapolation of how these techniques should be applied to the infrastructure layer. I see members of communities push for rapid release cycles of infrastructure code. Usually these folks have little history with running large infrastructure systems.

When we look at large-scale infrastructure, the story—even for the web scale folks—is one of stability and consistency, not constant change. There is simply a different risk profile for infrastructure. For example, AWS is notorious for running forked versions of Xen 3.x after they were deprecated.[1] In fact, AWS rarely, if ever updates the Xen hypervisor due to the inherent risk.

Differing Risk Profiles

A web application and infrastructure systems have different risk profiles. If your application has a bug introduced that causes it to fail completely during an arbitrary update, you still have the ability to talk to the infrastructure. That means you can “roll forward” or reload your application onto the infrastructure from scratch in a worst case scenario. All of this is usually fully automated.

On the other hand, a failure of the core infrastructure, like storage or networking, could cause a catastrophic failure that would preclude reloading the system trivially. Yes, you could wipe the bare metal and reset if you have access to the metal, but you are talking about a significant amount of time to reset. Or, say for example, that you were using a software virtualization technique such as software-defined-networking (SDN) or software-defined-storage (SDS) for networking and storage. What happens if you bring your SDN system down hard and can no longer reach the control plane? Or if you introduce a software bug to your SDS that actively damages your datasets causing you to have to reload from backups or resynchronize from a secondary system?

Infrastructure simply has a different risk profile and requires you to be more careful, to do more active up front testing, and to be more certain about code updates.

Cloud Dependency Model

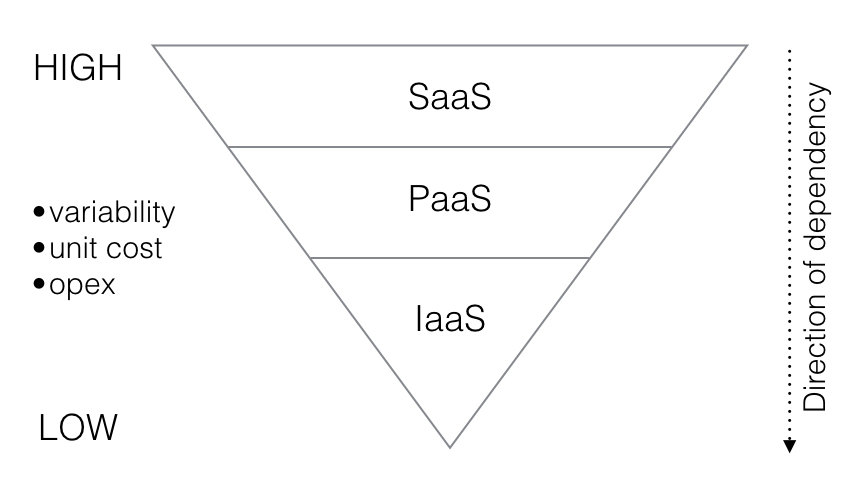

The following diagram highlights these differences.

You have probably seen the traditional cloud pyramid at some point. When considering differences in risk it is best to understand dependency. All applications and services depend on infrastructure at some layer, whereas infrastructure (compute, storage, and network) have no dependency whatsoever on the apps that run on top of them. Catastrophic failures at lower levels will impact apps running above, usually many apps.

It’s also important to understand that part of what the web-scale cloud computing pioneers like Google and Amazon taught us is that infrastructure should be relatively homogeneous (“homologous”). Google can manage 10,000 physical servers with a single admin because they only have a handful of configurations. This persists across all cloud infrastructure. Typically the cost per unit, the variability of the configurations, and the cost to operate are all low.

Applications and services however are more costly to operate, the cost to develop them is higher as by definition they are bespoke, being written from scratch to drive critical business functions, and variability between different kinds of applications is high.

In other words, apps are only dependent on other apps, are closer to customers, are bespoke and highly heterogeneous, requiring regular rapid releases and roll-forward methodologies.

So when we think about these things we need to realize that because platforms and apps are dependent on infrastructure a high rate of change creates more risk. We do want to be able to update infrastructure faster than in the past, but hourly, daily, and even weekly changes introduce the possibility of catastrophic failures. More vetting is inherently required.

What does that look like?

How OpenContrail is Tested

Juniper’s OpenContrail is an example of an enterprise-grade infrastructure software product. Because any given commit to OpenContrail could potentially cause a catastrophic failure, bringing an entire cloud to its knees, significantly more rigor needs to be applied. Also, most enterprise-grade infrastructure provides a robust feature set, which means that not only must a given feature or code commit be tested, but ideally it is tested across a wide variety of hardware, software, and architectural configurations.

OpenContrail testing consists of:

- Unit tests for all code checkins (runs in minutes)

- Module tests (runs in minutes)

- Feature testing during development (variable run time, occasionally tied to dependencies around other software and hardware; e.g. DNS features tied to BIND)

- Light regression testing (our “sanity tests” that run in minutes to hours)

- Full regression testing (runs in 24 hours)

- Performance testing

- Scalability testing

- Upgrade testing

- End-to-end system tests (think OpenStack tempests; deploy the entire system in a variety of configurations and test feature functionality)

That’s a lot of testing. End-to-end, to complete all testing takes roughly a month of time. As code is checked in, unit tests, module tests, feature tests, and light regression tests are all kicked off in an automated fashion for that build. For small changes this usually but not always, means that the resulting build is usable, at least for non-production concerns.

However, for a specific code check-in at any point in time we still haven’t run full regression, performance, scalability, upgrade, or end-to-end system tests.

Why does this matter? Let’s look at just a couple of examples. For performance tests we need to automatically deploy and setup an OpenContrail-based system and then measure a huge number of different performance metrics, including, but not limited to:

- Flow setup rate

- Ping latency

- TCP throughput

- UDP throughput

- TCP transaction rate

- and much more

For end-to-end system tests, we have to automatically deploy and setup an OpenContrail-based system and then check all of its various feature/functions to validate that none were broken, including, but not limited to:

- Policy flows

- NAT flows

- Routed underlay networks

- Floating IP

- MPLS over (UDP or GRE) and VXLAN encapsulation

- Mgmt & control/data separation

- Bonded interfaces

- High availability of the control plane

- ECMP with service instances

- NAT service instance

- L2 firewall service instance

- Dynamic ACL & service instance-based mirroring

- The GUI, configuration of the system, network monitoring, and analytics

- Multiproject traffic

- Security groups

- VM static routes

- Multi-tenancy

- Test supported orchestration system (OpenStack, VMware, Kubernetes (soon))

- … and so much more than this

Does all of this need to be tested for every code check-in? No. But the larger the code that is checked in or the closer it is to a critical system (e.g. database schemas), the more likely there is to be a side-effect that is unexpected. Now remember, if this was at the app layer, we could push with less testing, because we can always fix and roll forward. At the infrastructure layer if we push and it breaks, we’re done.

The Need for Speed

I get it. You want to go fast. Really fast. That means you want to update your infrastructure layer features more frequently. Frankly, you should be able to. This is a new age and the need for speed is an imperative for us all. If you are a carrier, telco, or cable operator you feel the need, in particular, to get rapid updates to your network infrastructure. We see these requests at Juniper Contrail all the time. You’re right, you shouldn’t have to wait to update your network once a year or once every two years. But asking to update your network every hour, every day, or every week is a recipe for significant downtime.

There is a sweet spot. Quarterly updates for major feature changes and monthly updates for security fixes will increase your overall velocity, while keeping risk to a tolerable minimum. Any faster and you’ll be bleeding customers.

A Busted Myth

It is sad to see the story of the rapid DevOps CI/CD pipeline extrapolated unnecessarily to the infrastructure layer. Companies, pundits, and DevOps leaders are creating a climate that leads to greater downtime by taking this approach. It is not proven in production anywhere. Large scale infrastructure businesses with high uptime like Google and Amazon simply aren’t doing this and for good reason: the risk profile for infrastructure is different than the applications that run on top of that infrastructure.

They do however develop CI pipelines and secondary non-production systems that take regular infrastructure code updates so that they can do extensive testing before rolling out infrastructure code updates. It’s not uncommon for large infrastructure code updates to be tested for many months before being rolled out. The risk is simply too high that if something goes wrong there will be significant down time or data loss.

Calibrate your DevOps thinking to bring risk to the equation. CI/CD without risk assessment is foolhardy.

[1] Also see What happens inside AWS when there is a Xen vulnerability