The 6 Requirements of Enterprise-grade OpenStack, Part 2

In part 1 of this series earlier this week, I introduced The 6 Requirements of Enterprise-grade OpenStack. Today, I’m going to dig into the next two major requirements: Open Architectures and Hybrid Cloud Interoperability.

Let’s get started.

Requirement #3 – Open Architectures & Reducing Vendor Lock-in

We already covered building a robust control plane and cloud management system. One of the attractions of OpenStack is removing vendor lock-in by moving to an open source platform. This is a key value proposition and deserves a complete dialog about what is realistic and what is not in an Enterprise-grade version of OpenStack.

“No Vendor Lock-in” is Snake Oil Salesmanship

Are you being promised that OpenStack provides “no lock-in?” No vendor lock-in is a platonic ideal - something that can be imagined as a perfect form, but never achieved. Any system always has some form of lock-in. For example, many of you probably use RedHat Enterprise Linux (RHEL), a completely 100% open source Linux operating system, as your default Linux within your business. Yet, RHEL is a form of lock-in. RHEL is a specific version of Linux designed for a specific goal. You are locked into their particular reference architecture, packaging systems, installers/bootloaders, etc., even though it is open source.

In fact, with many customers I have seen less of a fear about lock-in and more of a concern about “more lock-in.” For example, one customer, who will remain anonymous, was concerned about adopting our block storage component, even though it was 100% open source due to lock-in concerns. When probed, it became clear that what the customer wanted was to use their existing storage vendors (NetApp and Hitachi Data Systems) and did not want to have to train up their IT teams on a completely new storage offering. Here the lock-in concerns were predominantly about absorbing more lock-in rather than removing it entirely.

What is most important is assessing the risks your business can take. Moving to OpenStack, as with Linux before it, means that you are mitigating certain risks in terms of training your IT teams on the new stack and hedging your bets by being able to get multiple vendors in-house to support your open source software.

In other words, OpenStack can certainly reduce lock-in, but it won’t remove it. So, demand an open architecture, but expect an enterprise product.

Lock-in Happens, Particularly with Enterprise Products

I wish it didn’t, but lock-in does happen, as you can see from above. That means that rather than planning for no lock-in, start planning for what lock-in you are comfortable with. An Enterprise-grade version of OpenStack will provide a variety of options via an open architecture so you can hedge your bets. However, a true cloud operating system and enterprise product cannot ever provide an infinite variety of options. Why not? Because then the support model is not sustainable and that vendor goes out of business. Not even the largest vendors can provide all options to all people.

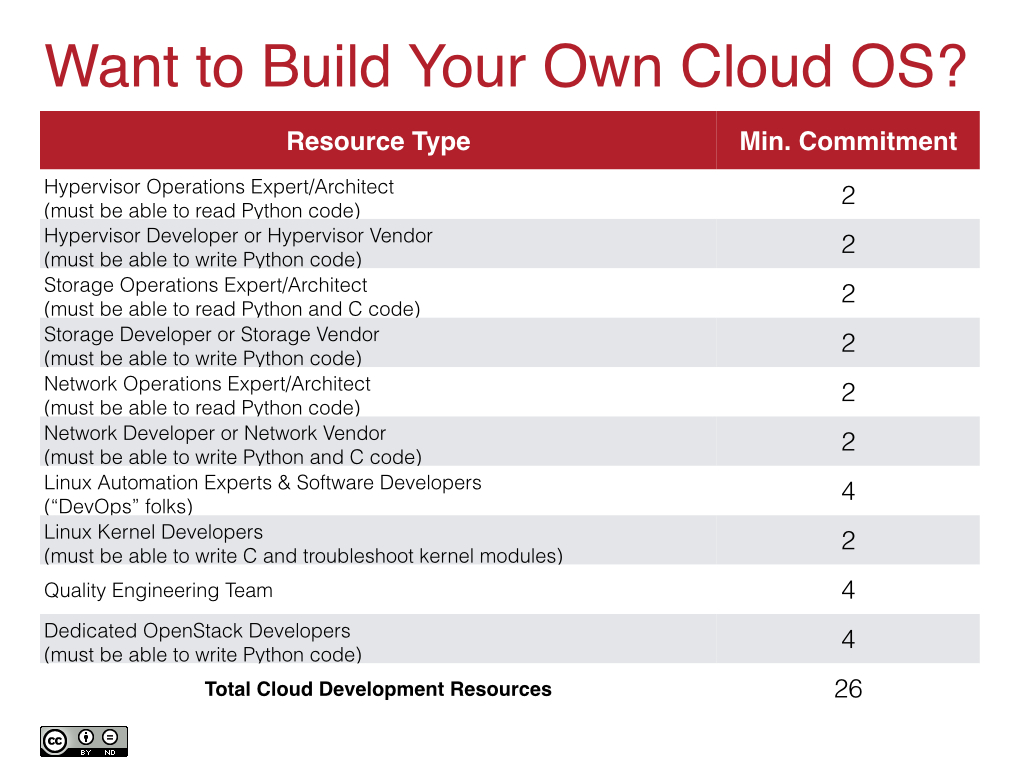

If you want to build your own customized cloud operating system[1] built around OpenStack, go ahead, but that isn’t a product. That’s a customized professional services path. Like those who rolled their own Linux distributions for a while, it leads to a path of chaos and kingdom-building that is bad for your business. Doing it yourself is also resource intensive. You’ll need 20-30 Python developers with a deep knowledge of infrastructure (compute, storage, and network) who can hack full time on your bastardized version of OpenStack. A team that looks something like this:

So, ultimately, you’re going to have to pick a vendor to bet on if you want enterprise-grade OpenStack-powered cloud solutions.

Requirement #4 – Hybrid Cloud Interoperability

Hybrid is the new cloud. Most customers we talk to acknowledge the reality of needing to provide their developers with the best tool for the job. Needs vary, requirements vary, concerns vary, compliance varies. Every enterprise is a bit unique. Some need to start on public cloud, but then move to private cloud over time. Some need to start on private, but slowly adopt public. Some start on both simultaneously. RightScale’s recent State of the Cloud 2014 report has some great survey data backing this up:

Let’s talk about why your enterprise-grade OpenStack-powered cloud operating system vendor had better have a great hybrid cloud story.

A Hybrid-first Cloud Strategy

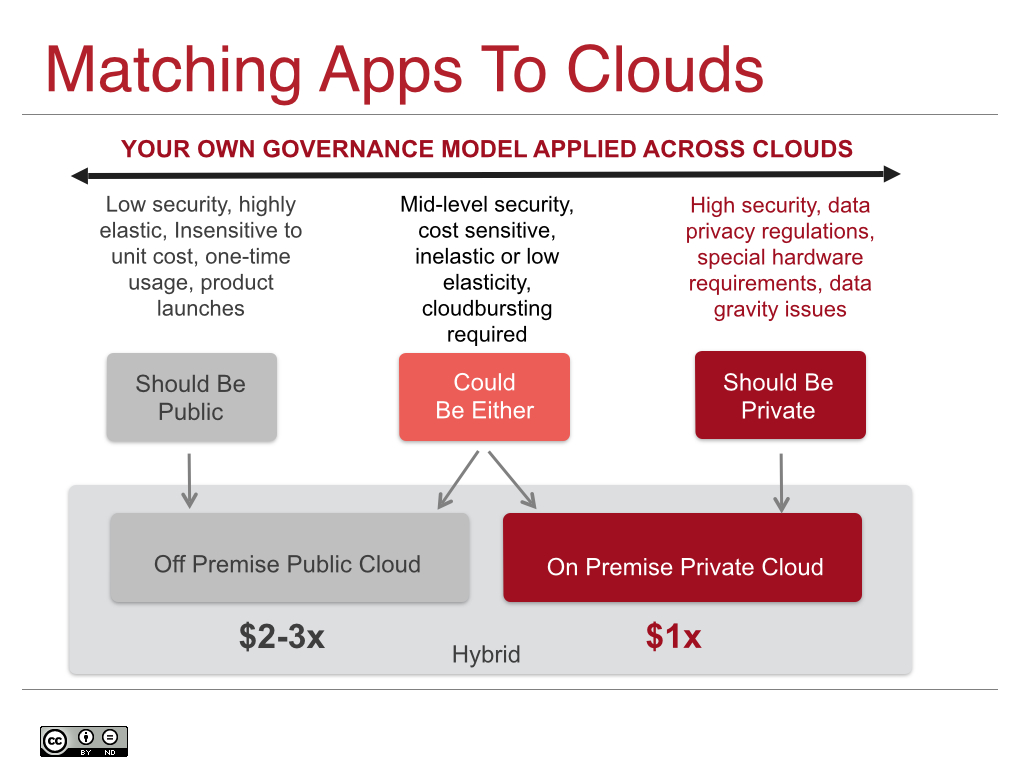

Every enterprise needs a hybrid-first cloud strategy. Meaning, hybrid cloud should be your first and primary requirement. Then, plan around hybrid with a single unified governance model that delivers the best of both world’s for your constituencies. Finally, plan on a process where you will triage your apps/needs and determine which cloud is right for the job. The following diagram highlights this process, but your mileage may vary as criteria are different from business to business:

Understanding Cloud Interoperability & It’s Role In Hybrid Cloud

I have been through quite a number of interoperability efforts, the most painful of which was IPSEC for VPNs. Interoperability between vendors is not free, usually takes a fairly serious effort, and ultimately is worth the pain. Unfortunately, interoperability is deeply misunderstood, particularly as it applies to public/private/hybrid cloud.

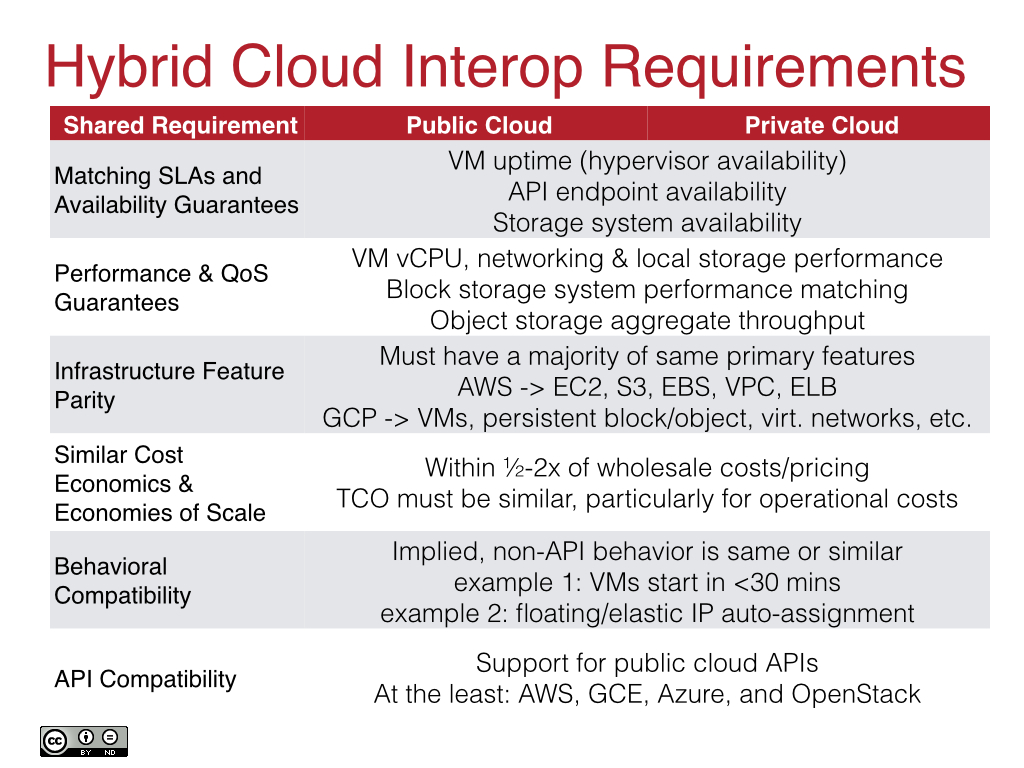

The challenge in hybrid cloud is about addressing the issues of application portability. If you want a combination of public and private clouds (hybrid) where an application can be deployed on either cloud, moved between the clouds, or cloudbursted from one cloud to another, then application portability is required. When you pick up and move an app and it’s cloud native automation framework[2] from one cloud to another, a number of key things need to remain the same:

-

Performance must be at relative parity

-

Underlying network, storage, and compute architectures must be the same or similar

-

Your automation framework must support API compatibility with both clouds

-

The TCO of running the app must be within ½-2x of each other

-

There must be behavioral compatibility, meaning non-API “features” are matched

-

You must support API compatibility with the relevant public clouds

Here is a slide I used in a recent webinar to help explain these requirements.

Of course, you must also have been thoughtful when designing your application and avoided any lock-in features of a particular cloud system, such as a reliance on DynamoDB on AWS, HA/DRS on VMware, iRules on F5 load balancers, etc.

If you don’t meet these requirements, interoperability is not possible and application portability attempts will fail. The application performance will be dramatically different and one cloud will be favored; there will be missing features that cause the app to not function on one cloud or another; and your automation framework may fail if behavioral compatibility doesn’t exist. For example, perhaps it has timers in it that assume a VM comes up in 30 minutes, but on one of your clouds it takes 1-2 hours (I’ve seen this happen).

All of these issues must be addressed in order to achieve hybrid cloud interoperability.

OpenStack Needs a Reference Architecture

The Linux kernel needs a reference architecture. In fact, each major distribution of Linux in essence creates it’s own reference architecture and now we have distinct flavors of Linux OS. For example, there are the RedHat/Fedora/CentOS flavors and the Debian/Ubuntu flavors. These complete x86 operating systems have fully-baked reference architectures and anyone moving within one of the groups will find it relatively trivial to move between them. Whereas a RedHat admin moving to Debian may initially be lost until they come up to speed on the differences. OpenStack is no different.

OpenStack, and in fact most of its open source brethren, has no reference architecture. OpenStack is really the kernel for a cloud operating system. This is actually its strength and weakness. The same holds for Linux. You can get Cray Linux for a supercomputer and you can get Android for an embedded ARM device. Both are Linux, yet both have radically different architectures, making application portability impossible. OpenStack is similar, in that to date most OpenStack clouds are not interoperable, because each has its own reference architecture. Every cloud with its own reference architecture is doomed to be an OpenSnowFlake.

Enterprise-grade cloud operating systems powered by OpenStack must have commonly held reference architectures. That way you can be assured that every deployment is interoperable with every other deployment. These reference architectures have yet to arise. However, given that there is already a single reference architecture in Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud Platform (GCP), (we call it “elastic cloud reference architecture”) and given that these two companies will be major forces in public cloud, it’s hard to see how OpenStack can avoid supporting at least one reference architecture that looks like the AWS/GCP model.

To be clear, however, there may be a number of winning reference architectures. I see emerging flavors in high performance computing (HPC) and possibly other verticals like oil & gas.

Enterprise-grade Reference Architecture

Ultimately, you have to place your own bet on where you think OpenStack lands, but existing data says that out of the top 10 public clouds, only a couple are based on OpenStack[3]:

If enterprises desire agility, flexibility, and choice, it seems obvious that OpenStack needs to support an enterprise-grade reference architecture that is focused on building hybrid clouds with the ultimate winners in public cloud. It’s just my opinion, but right now that looks like Amazon, Google, and Microsoft.

Enterprise-grade OpenStack means an enterprise-grade reference architecture that enables hybrid cloud interoperability and application portability.

Part 2 Summary

An open architecture designed for hybrid cloud interoperability is a foregone conclusion at this point. Mostly what folks argue about is how that will be achieved, but for those of us who are pragmatists, it’s certain that public cloud will have a wide variety of winners and that the top 10 public clouds is already dominated by non-OpenStack contenders. So plan accordingly.

Most importantly, remember to ask for an open architecture, while expecting an enterprise product.

In the next installment we’ll tackle what it means to deliver a performant, scalable, and elastic infrastructure designed for next gen apps.

Next Installment:

UPDATE: Added a clarifying footnote due to some Twitter feedback that seemed unclear on what a “cloud operating system” was and it’s relationship to OpenStack and similar open source projects.

[1] No, Eucalyptus, OpenNebula, CloudStack,

[2] By definition any cloud native next gen app manages itself via an automation framework. It might be a low level approach like Chef, Puppet, SaltStack; it might be a higher order abstraction like Scalr, RightScale, Dell Cloud Manager; it might even be a PaaS framework, but it’s something. Or it’s not a cloud-native app.

[3] Be sure to read the caveats on the VMware vCHS data in the actual report itself.