Killing the Storage Unicorn: Purpose-Built ScaleIO Spanks Multi-Purpose Ceph on Performance

Collectively it’s clear that we’ve all had it with the cost of storage, particularly the cost to maintain and operate storage systems. The problem is that data requirements, both in terms of capacity and IOPS are exploding and growing exponentially, while the cost of storage operations and management is growing proportionally to those data needs. Historically the biggest culprit is “storage sprawl” where we have pairs of arrays throughout the datacenter, each of which has to be managed individually. Silo after silo, requiring specialized training, its own HA and resiliency, monitoring, and so on. It’s for this reason that many turned to so-called “unified storage.” This, unfortunately, is a terrible idea for larger deployments and those running production systems.

Let me explain.

The Storage Unicorn & a Rational Solution

We all want what we can’t have: a single globally distributed, unified storage system, that is infinitely scalable, easy to manage, replicated between datacenters and serves block devices, file systems, and object, all without hiccups. Bonus points if you throw in tape as well! This is the Storage Unicorn. No such beast exists and never will. Even before the EMC acquisition of Cloudscaling I was talking about these issues in my white paper: The Case for Tiered Storage in Private Clouds.

The nut of that white paper is that tier-1, mission critical storage, is optimized for IOPS, while tier-3 is optimized for long term durability. Think of flash vs. tape. These are not the same technologies nor can they serve the same purpose or use cases.

A multi-purpose tool is great in a pinch, but if you need to do real work, you need a purpose-built tool:

The issue remains though; how do we reduce storage management costs and manage the scaling of storage in a rational manner? There is no doubt, for example, that the multi-purpose tool is lower overhead. It’s simply less things to manage. That is a pro and a con.

The challenge then is to walk away from the Unicorn. You can’t have a single storage system to solve all of your woes. However, you probably don’t have to live with tens or hundreds of storage systems either.

Dialing down your storage needs to a small handful of silos would probably have a dramatic effect on operational costs! What if you only had something like this in each datacenter:

-

Scalable distributed block storage

-

Scalable distributed object storage

-

Scalable distributed file system storage

-

Scalable control plane that manages all of the above

There isn’t any significant advantage in driving these four systems down to one. The real optimization is from tens or hundreds of managed systems to a handful. Everything else is unnecessary optimization at best or mental masturbation at worst. Perhaps most egregiously, any gut check tells us that while 100 -> 4 managed systems is likely a 10x change in cost of management, 4 -> 1 is probably a small fraction of savings by comparison. [1]

Multi-Purpose Tool Example: Taking A Look at Ceph’s Underlying Architecture

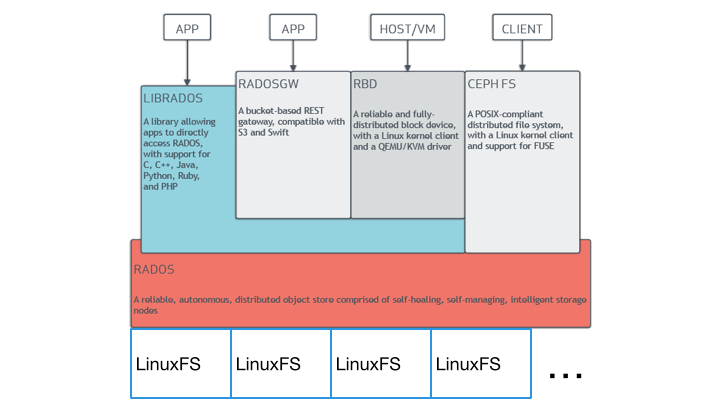

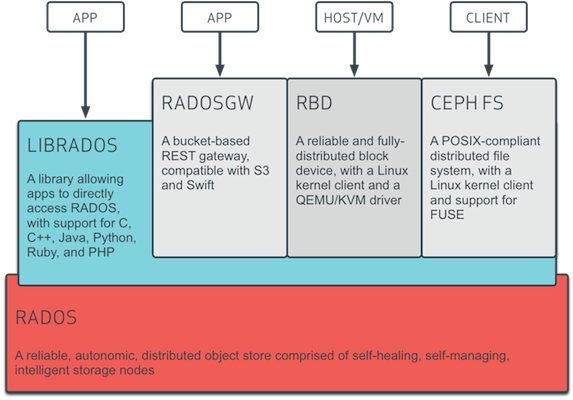

The fundamental problem with any multi-purpose tool is that it makes compromises in each “purpose” it serves. Multi-purpose tools do this because two tools frequently are designed for different purposes. If you want your screwdriver to also be a hammer, you have to make some kind of tradeoff. Ceph’s tradeoff, as a multi-purpose tool, is the use of a single “object storage” layer. You have a block interface (RBD), an object interface (RADOSGW), and a filesystem interface (CephFS), all of which talk to an underlying object storage system (RADOS). Here is the Ceph architecture from their documentation:

Glossed over is that RADOS itself is reliant on an underlying filesystem to store its objects. So the diagram should actually look like this:

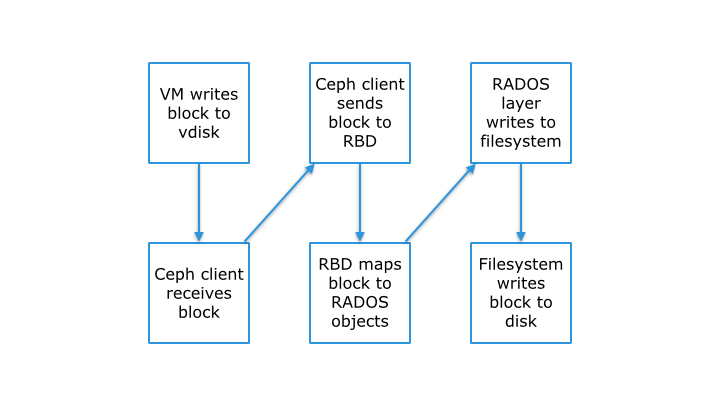

So in a given data path, for example a block written to disk, there is a high level of overhead:

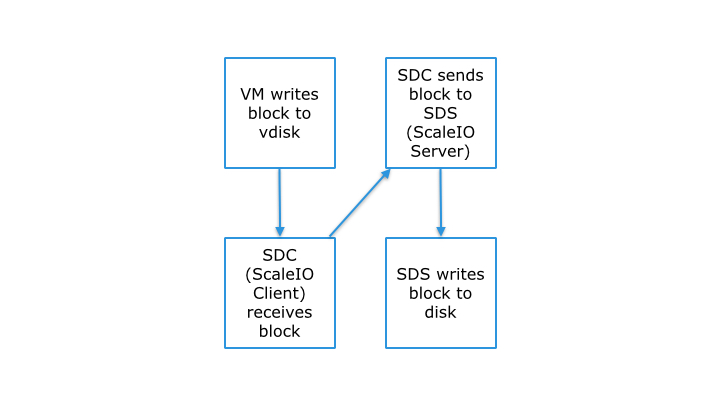

In contrast, a purpose-built block storage system that does not compromise and is focused solely on block storage, like EMC ScaleIO, can be significantly more efficient:

This allows skipping two steps, but perhaps more importantly, it avoids complications and additional layers of indirection/abstraction as there is a 1:1 mapping of the ScaleIO client’s block and the block(s) on disk in the ScaleIO cluster.

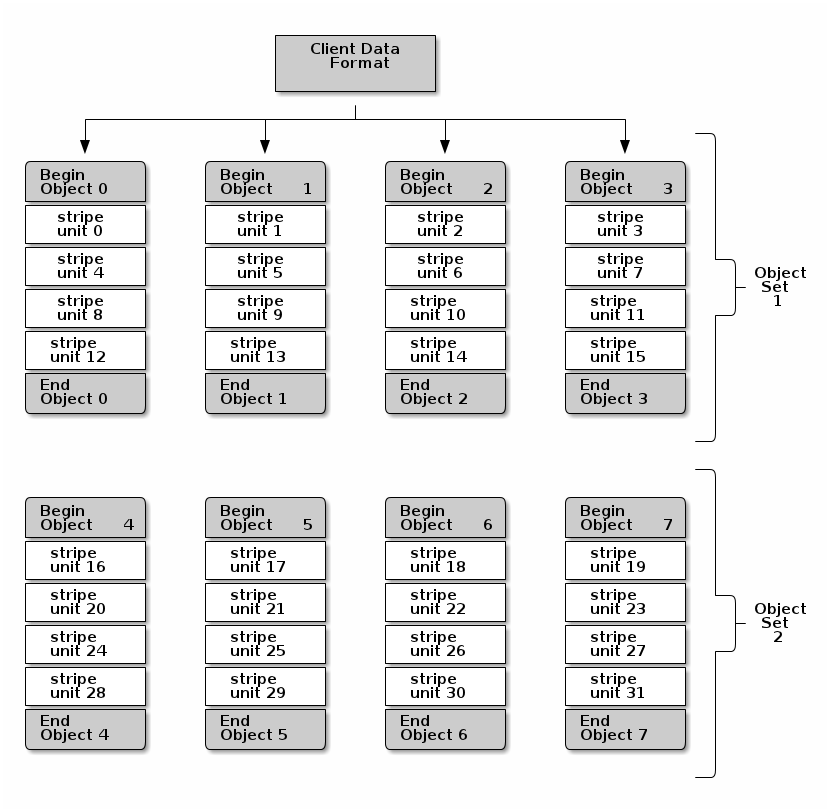

By comparison, multi-purpose systems need to have a single unified way of laying out storage data, which can add significant overhead. Ceph, for example, takes any of its “client data formats” (object, file, block), slices them up into “stripes”, and distributes those stripes across many “objects”, each of which is distributed within replicated sets, which are ultimately stored on a Linux filesystem in the Ceph cluster. Here’s the diagram from the Ceph documentation describing this:

This is a great architecture if you are going to normalize multiple protocols, but it’s a terrible architecture if you are designing for high performance block storage only.

Show Me the Money!

We recently put our performance engineering team to the task of comparing performance between Ceph and ScaleIO. Benchmarks are always difficult. A lot depends on context, configuration, etc. We put our best performance engineers on the job though, just so we could see if our belief that a purpose-built block storage system was better than a multi-purpose Swiss army knife.

-

Goal: evaluate block performance between Ceph and ScaleIO as fairly as possible

-

Assumptions: same hardware (servers, drives, network, etc.) and same logical configuration (as best as possible)

-

Test cases: “SSD only”, “SSD+HDD”, and “hybrid mode” with SSD as cache for HDD

-

Workload: 70% reads / 30% writes with 8KB blocks

-

Test tool: FIO with shallow (1) and deep (240) queue depths

Ceph Configuration

-

Ceph “Giant” release 0.87

-

Publicly available Ceph packages from ceph.com

-

(4) Storage Nodes, each configured with

-

2 OSD’s (SSD pool) = 2 x 800GB SSD

-

12 OSD’s (HDD pool) = 12 x 1TB HDD + 2 x 800GB SSD

-

-

(4) RBD Clients

-

1 x 200GB device (/dev/rbdX) (one small volume per client)

- various pools, SSD, HDD, and HDD with Ceph writeback cache tiering, inflated prior to testing (not thin)

-

1 x 4TB device (/dev/rbdY) (one large volume per client)

- HDD pool with and without writeback cache tiering, inflated prior to testing (not thin)

-

-

(1) Monitor Node

-

Not required for ScaleIO

-

Three usually recommended for HA purposes, but some loss in performance for metadata syncing, so only one used for testing

ScaleIO Configuration

-

Used v1.31 of ScaleIO

-

(4) ScaleIO Storage Server Nodes (SDS), each configured with

-

1 SSD Storage Pool = 2 x 800GB SSD

-

1 HDD Storage Pool = 12 x 1TB HDD

-

HDD Storage Pool uses SSD storage pool for caching only in final tests

-

For the cases where SSD was used as cache, we waited for the cache to warm up and because the volume was smaller than cache, all the IOs made it to cache at the end

-

-

-

(4) ScaleIO Data Clients (SDC)

-

1 x 200GB volume mapped to SSD pool

-

1 x 4TB volume mapped to HDD pool

-

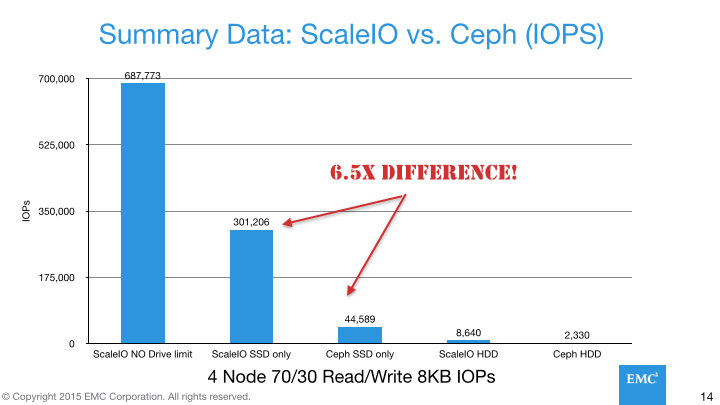

Summary Findings: ScaleIO vs. Ceph (IOPS)

As you can see from the following diagram, in terms of raw throughput, ScaleIO absolutely spanks Ceph, clocking in performance dramatically above that of Ceph [2].

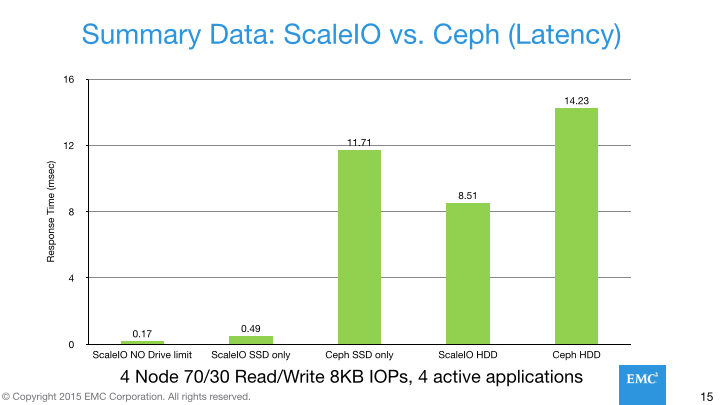

In terms of latency, Ceph’s situation is much grimmer, with Ceph having incredibly poor latency, almost certainly due to their architecture compromises. Even with SSDs, Ceph’s latency is worse than what you would expect from a single HDD (~7-10ms); moreover Ceph’s latency with SSD is actually worse than ScaleIO using HDD. This is unbelievably poor. An SSD-based storage system should have latency in the ballpark of an SSD and even if there is some kind of performance penalty, it shouldn’t be more than 10x.

It’s About More Than Performance

There are other problems besides performance with a multi-purpose system. The overhead I outlined above also means the system has a hard time being lean and mean. Every new task or purpose it takes on includes overhead in terms of business logic, processing time, and resources consumed. In most common configurations, ScaleIO, being purpose-built takes as little as 5% of the host system’s resources such as memory and CPU. In most of our testing we found that Ceph takes significantly more, some times as much as 10x the resources as ScaleIO, making it a very poor choice for “hyperconverged” or semi-hyperconverged deployments.

This means that if you built two separate configurations of Ceph vs. ScaleIO that are designed to deliver the same performance levels, ScaleIO would have significantly better TCO, just factoring in the cost of the more expensive hardware required to support Ceph’s heavyweight footprint. I will have more on this in a future blog posting, but again, it reinforces that purpose-built systems can be better not only on performance, but also on cost.

In the meantime, here’s the brief summary table I put together:

The numbers put together make the following basic assumptions:

-

Target capacity of 100TB usable storage

-

Use enough “storage servers” to meet capacity demands

-

Run the application on storage servers (hyperconverged)

-

Add additional application servers to meet apps processing and memory requirements as needed

- This is the 12+11 and 8+5 numbers above

-

Ceph configured for “performance” workloads, so using replication instead of erasure encoding

In this configuration, ScaleIO takes 43% less servers, uses 29% less raw storage to achieve the target storage, and cost per usable TB is 34% less. All of this while providing 6.5x the IOPS.

Obviously, the numbers here get a lot worse if you target total IOPS instead of usable capacity.

There will be a more in-depth blog posting looking at our calculator in-depth late August. I will be happy to share the spreadsheet at that time as well.

Summary

This blog posting isn’t about “Ceph bad, ScaleIO good”, although it will certainly be misconstrued as such. This is about killing Unicorns. Unicorns are bad if people think they exist or worse when they are being peddled by vendors. Unicorns are good if they stay in the realm of platonic ideals and hopeful goals. I will point you again to my previous white paper partially taking Ceph to task on their unified storage marketing message. Google still backs up to tape. Amazon has spinning disks and SSDs.

Information Technology (IT) is fundamentally about making tradeoffs. There is no silver bullet and taking the blue pill will only lead to failure. Real IT is about understanding these tradeoffs and making educated and informed decisions. You may need a Swiss army knife. Perhaps your requirements for performance are low. Perhaps you are building smaller systems that doesn’t need much scalability. Perhaps you don’t care about your total cost of ownership (TCO).

However, if you want to build a relatively low cost, high performance, distributed block storage system that supports bare metal, virtual machines, and containers, then you need something purpose built for block storage. You need a system optimized for block, not a multi-tool.

If you haven’t already, check out ScaleIO, which is free to download and use at whatever size you want. Run these tests yourself. Report the results if you like. [3]

[1] Not only that, but if you are serious, you can’t get down to 1 storage system anyway. Where will you back it up to? You need tape. Or at least another Ceph cluster. The DreamHost team, who runs Ceph in production and who were the original authors of the codebase run two Ceph clusters, taking backup snapshots from one and storing them in the other cluster and vice versa. So your minimum footprint is 2 storage systems, possibly 3 if you decide to build a unified management system as well. C’est la vie?

[2] Here “Null” or “no disk limit” refers to performing a baseline test removing all physical disk I/O from the equation and providing some idea of the absolute performance of the software itself, including network overhead. More here in the 3rd party ESG ScaleIO tests.

[3] The current ScaleIO EULA may preclude sharing this information publicly. I’m working with the EMC legal team and the ScaleIO product team to have this fixed. It looks like I will at least be able to get this done “with permission.” Email me if you have any questions.