Elasticity is NOT #Cloud Computing ... Just Ask Google

In my keynote presentation (free registration required to download) on Day 1 of the Enterprise Cloud Summit at Interop NYC last week some interesting comments followed up in person and on twitter. I think one particular notion that surprised people was the assertion that elasticity, a property commonly associated with ‘cloud’ and ‘cloud computing’, wasn’t a part of cloud computing, but rather a side effect.

This really goes back to the definition problem with cloud computing. I have alluded to this in the past; that the Cloudscaling definition is functionally different from many of the common definitions out there today, including the famous NIST definitions. Why do we think about this differently and why does that mean that elasticity is overblown as a property of cloud computing?

The rest of this post is an illustrated walk-through of our thinking. Please click through (below).

The Start of a Thought As many of you know, I’ve been working in the cloud computing space and blogging about this area for a very long time. When the definitional problems started, along with the bickering in mid-2008, I started thinking:

Are ‘cloud’ and ‘cloud computing’ the same? Is there commonality between SaaS, PaaS, and IaaS that we’re missing? What did Salesforce.com/Force, Amazon EC2/Amazon.com, and Google/Google App Engine all have in common?

The conclusion I came to was a sort of ‘aha!’ moment. I realized that the large web operators had essentially built whole new ways of building IT. Something that was fundamentally different to what went before. I also realized that a big part of why the definition problems existed is because the change was so massive that it was affecting everything in IT, not just some part, like storage or application development.

Finally, I also realized that the bottom layers of IT, particularly the most common ones used every where such as servers, storage, and networking, were being treated in a completely different way by Amazon, Google, and company. These folks were not following the standard play book. In some ways they were following the playbook with the layers above servers, storage, and networking. For example, they used standard programming languages to build their applications, such as Python and Java. These had not changed. The applications being provided were the same as those before, like e-mail, search, and recommendation systems. Storage, compute, and networks were very different, however as were the ‘platform’ layers directly above them that allowed ‘pooling’ of these resources (e.g. GoogleFS).

What really changed matters though is that many of these pioneers took a whole new approach to running the lower layers of IT: datacenter facilities, the infrastructure architecture, and the direct layer above physical resources that creates a common datacenter platform. Something Google calls warehouse computing (PDF), but we simply call “cloud computing.”

Public utility cloud providers exist because “warehouse” (cloud) computing is now possible at a massive scale for low cost. Commoditization begets utilitization. Something pioneered not by enterprise vendors, but by Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and the like.

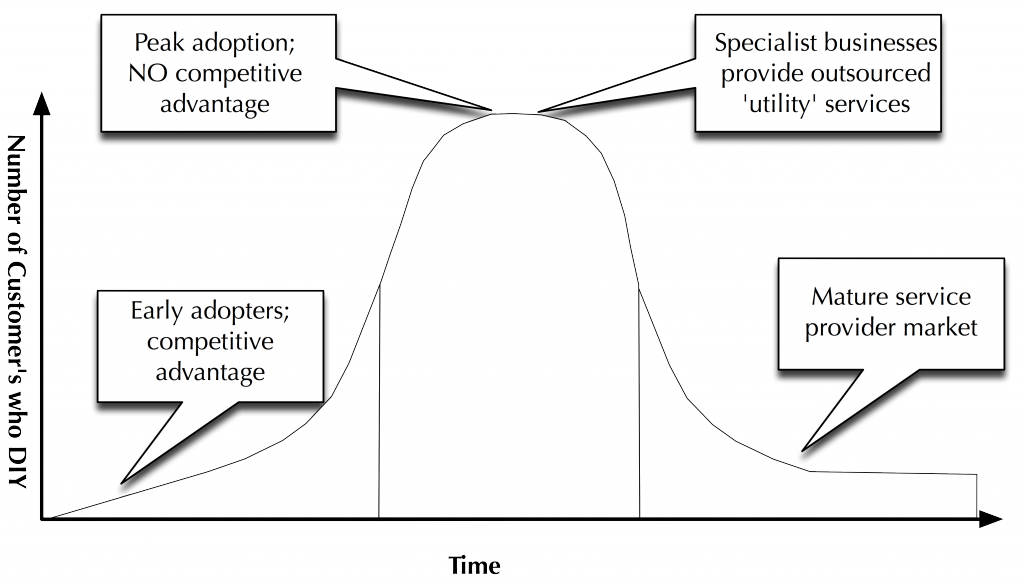

Cloud Computing as a Continuum of IT Infrastructure In Nick Carr’s famous book, Does IT Matter, he argued eloquently, providing copious examples, that most business infrastructure goes through a fairly common cycle. This cycle is well-understood and more of a force of nature than anything else. What we are seeing now with cloud computing is nothing more than this cycle replayed again with information technology (IT), just like it has with electricity, roads/highways, banking, and telecommunications before it.

Here is a diagram that illustrates the cycle.

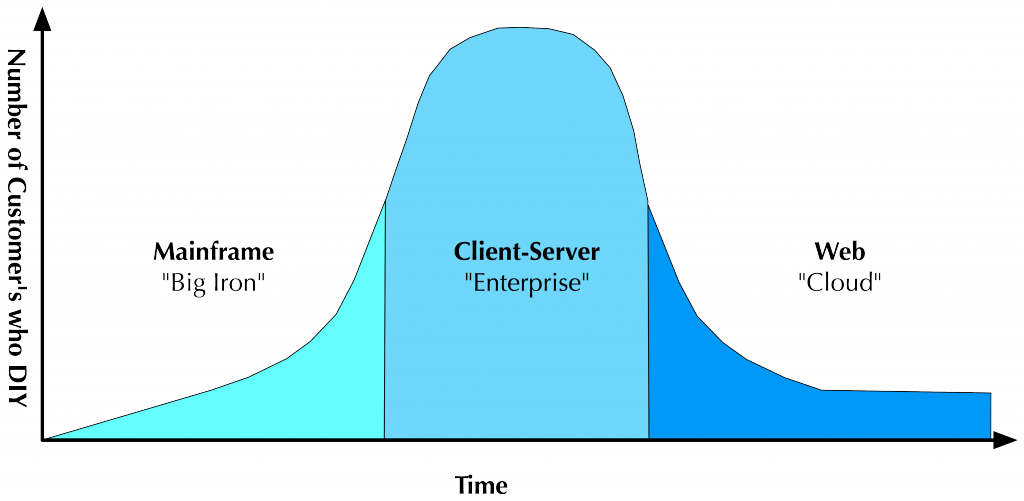

This cycle also maps directly to the three clear phases that we see with IT infrastructure:

I think this really says it all. For us, cloud computing is a whole new way of delivering IT services, particularly at the infrastructure level that does not look anything like what has come before. In the same way that Mainframe and Client-Server computing are very very different.

I think this really says it all. For us, cloud computing is a whole new way of delivering IT services, particularly at the infrastructure level that does not look anything like what has come before. In the same way that Mainframe and Client-Server computing are very very different.

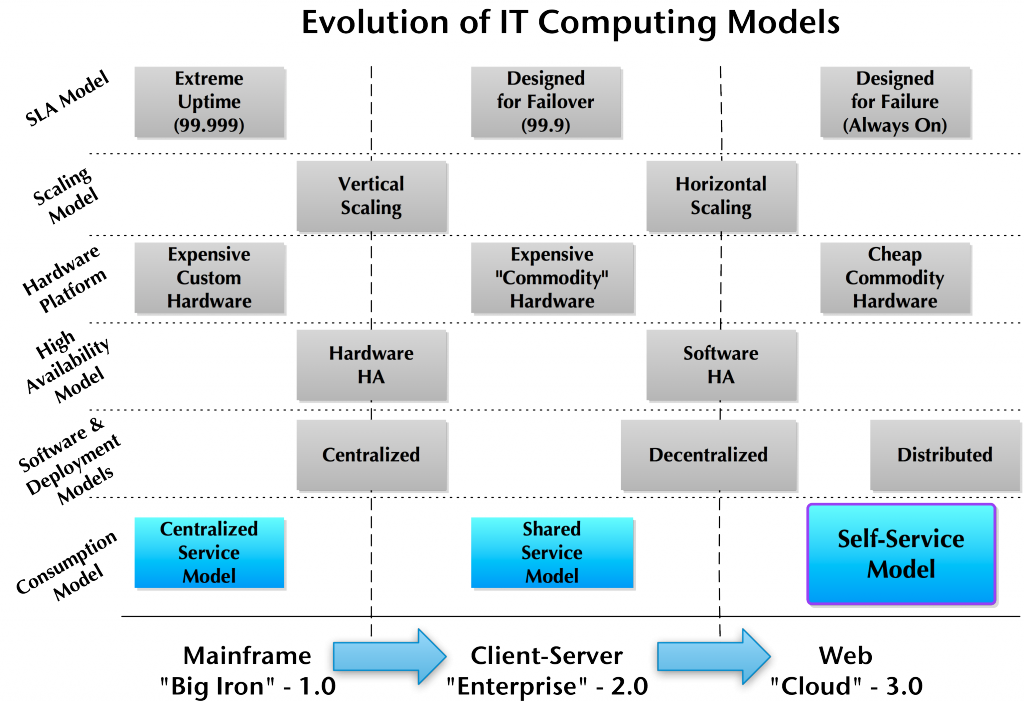

Another way to illustrate this is to look at the approaches that each of these take:

I’m not going to go into this matrix in detail right now, but whether you disagree with aspects or not, I’m certain you can see the trend occurring in the diagram. Cloud computing definitely appears to be an evolution of the way that we create IT.

Elasticity As Side-Effect Which brings me to the basic argument. If the following are true about cloud computing:

-

It is something new …

-

… developed by the giant web businesses in order to get to massive scale

-

… and an evolution of how IT infrastructure is created

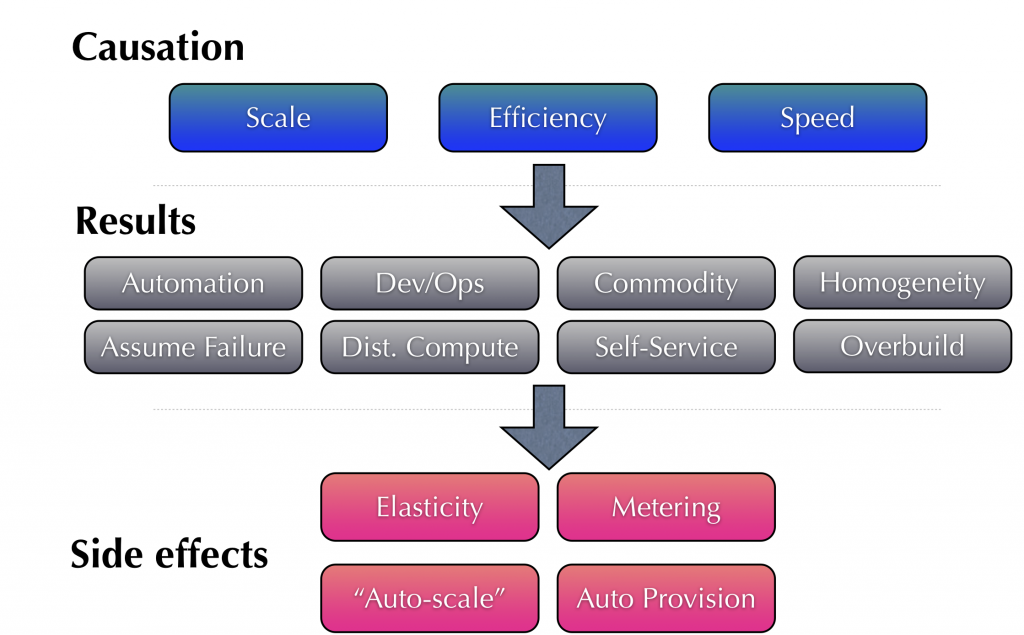

Then we have to look carefully at how and why an Amazon or Google did what they did. The diagram I used to explain during my keynote:

Large Internet business needed scale, cost-efficiency, and agility to be competitive. Google is 1 Million servers. Amazon.com releases new code thousands of times per day. Microsoft runs 2,000 physical servers per headcount. Google runs 10,000 per headcount and aspires for 100,000. Google and Amazon use little or no ‘enterprise computing’ solutions.

So what happened? The causation resulted in high levels of automation, a devops culture, use of standardized commodity hardware, a focus on homogeneity, etc. The end result is a system that lends itself to being turned into a utility (aka ‘utilitization’. Hence the arrival of public clouds. One of the side-effects of using cloud computing techniques to build an IT infrastructure is that now those platforms or applications built on top of it can leverage the automation to get elasticity (benefit), pay-only-for-what-you-use with metering (benefit), and other autonomous functions (benefit).

Again, these benefits are essentially side effects of cloud computing, not cloud computing itself. The gray section labeled results above represents a number of the core aspects and features of cloud computing. This is why the arguments about the existence of internal ‘private’ clouds can be so bitter[1]. From a public cloud provider perspective, an internal infrastructure cloud is simply an automated virtual server on-demand system, missing many of the aspects of cloud computing above.

Conclusion Are on-demand automated virtual machines an infrastructure cloud? I would argue no. That’s not ‘new’. Again, we need to look at what the large web businesses such as Amazon and Google did that has changed the game. It wasn’t elasticity, it wasn’t automation, and it wasn’t virtual machines. It was a whole new way of providing and consuming information technology (IT). If you aren’t following that path, you aren’t building a cloud.

Ask yourself, before you buy that new shiny hardware appliance or enterprise vendor cloud-washed hardware solution:

“What would Google do?”

[1] Don’t miss my post earlier this year on private clouds.